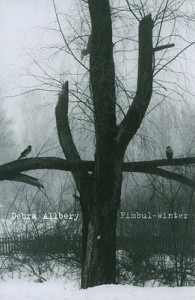

Book of the Week: Fimbul-Winter, by Debra Allbery

BY JEREMIAH CHAMBERLIN

This week’s feature is Debra Allbery’s new poetry collection, Fimbul-Winter. The book was published last year by Four Way Books and was the recipient of the 2010 Grub Street National Poetry Prize. Allbery is also the author of a previous collection of poems,Walking Distance, which won the Agnes Lynch Starrett Prize from the University of Pittsburgh. New poems are forthcoming in theChronicle of Higher Education, Virginia Quarterly Review, and The Kenyon Review. She lives near Asheville, NC, and is the Director of the MFA Program for Writers at Warren Wilson College. She is also a recent contributor for Fiction Writers Review, writing on the influence that Sherwood Anderson’s life and work had on her development as a young poet.

This week’s feature is Debra Allbery’s new poetry collection, Fimbul-Winter. The book was published last year by Four Way Books and was the recipient of the 2010 Grub Street National Poetry Prize. Allbery is also the author of a previous collection of poems,Walking Distance, which won the Agnes Lynch Starrett Prize from the University of Pittsburgh. New poems are forthcoming in theChronicle of Higher Education, Virginia Quarterly Review, and The Kenyon Review. She lives near Asheville, NC, and is the Director of the MFA Program for Writers at Warren Wilson College. She is also a recent contributor for Fiction Writers Review, writing on the influence that Sherwood Anderson’s life and work had on her development as a young poet.

Like Anderson, Allbery grew up in Clyde, Ohio, the small town that served as the model for Winesburg, Ohio, and the stories in his famed 1919 collection of the same name. In her essay “A Story Teller’s Story, A Poet’s Beginnings,” Allbery writes of this place and her childhood:

In many ways, Clyde in the 1960s still resembled the town that Anderson had known (he left it in 1897), a place anchored by a stubborn stasis and insularity which was both comforting and exasperating. The Presbyterian Church’s bell tower was screened in by then (no longer having, if it ever did, the stained glass window Reverend Hartman broke in “The Strength of God”). But the town still had its hitching rails in place along Main Street when I was little, many of the streets were brick (I loved the cobble-cobble of tires passing over them), the dime store its original pressed-tin ceiling. And there was a long-defunct grain elevator in the middle of town, right by the railroad tracks that people had once believed would transform Clyde into a Cleveland or a Columbus.

It wasn’t until Allbery was an adolescent, however, that Anderson and his work entered her awareness. Her father, “a champion reader,” brought home a college literature textbook that he’d picked up at a garage sale. “Red cloth binding and about four inches thick,” she writes, “it included some Anderson’s stories—“I’m a Fool,” “I Want to Know Why,” and “A Death in the Woods.” She continues:

My father pointed out Anderson’s name in the table of contents and said, “This man grew up in Clyde.” It’s difficult to describe the enormity of the impact that had on me then, and thereafter—the possibility it fostered in me, the nascent sense of kinship. “I’m a Fool” and “I Want to Know Why” left me with an empty and unsettled sadness, but “Death in the Woods” felt like a folktale. I was as drawn toward the narrator’s need to tell the story as to the story itself. It would become a kind of touchstone for years; returning to it and reentering it, understanding more of what it had to offer, I began to see it as a barometer of my own growth as a writer, and a measure of how much farther I still had to go.

In her conclusion to this essay, Allbery returns to the place and author who would so fundamentally shape her career, writing:

It’s the Anderson of “Death in the Woods” that feels most like my forebear, my kin—if Melville is Anderson’s grandfather, I’ve long felt that Anderson is mine…Anderson’s fiction, the landscape of his stories, is the place I come from—in the same way that I’d later feel I came, as well, from the worn, industrial landscapes and perspectives of the poems of James Wright, who said, “The spirit of place…isn’t simply image but presence…the genius of place.”

Though perhaps no homage to Anderson is more fitting than Allbery’s poetry itself. Here is Section 4 of “In the Pines,” from Fimbul-Winter, reprinted with permission from Four Way Books:

Death in the Woods

The story is about the storyteller,

about getting the telling right.The narrator is recalling the winter

he and his brother, just boys, found a womanfrozen to death in the woods.

She’s been made old before her timeby a hard life, hard men. She’s beautiful

in death, of course. Her clothes worriedfrom her body by a pack of dogs

that have circled her dying, left an iced zeroaround her in the clearing. It’s that circle

in the story that always gives me solace,the drumbeat of that path, the dogs running

nose to tail. And the boy, now a man,can’t stop telling this story. He invents a life

for the woman in an effort toward honor,he erases it and starts again because

to be done with it is a disservice. The pointof the story is to keep her cold mystery,

keep that circle drawn around herhigher and higher, a glass wall, keep everyone

from getting any closer.